In the sprawling landscape of agile methodologies, where frameworks often compete with elaborate ceremonies and rigid structures, the Crystal method stands apart as refreshingly human-centered. While Scrum champions its sprints and Kanban celebrates its visual boards, Crystal takes a fundamentally different approach: it trusts teams to figure out what works best for them.

This philosophy might sound almost too simple in our process-obsessed world, but therein lies Crystal’s quiet power. Rather than prescribing a one-size-fits-all solution, it acknowledges a truth that many organizations struggle to accept—every project is genuinely unique, and the people working on it are best positioned to determine how that work should unfold.

What is the Crystal Method?

Crystal represents a distinctive approach within the agile family, one that places individuals and their interactions at the absolute center of the development process. This isn’t merely paying lip service to the Agile Manifesto’s values—it’s a framework that was built from the ground up around the premise that processes and tools should serve people, not the other way around.

The framework rests on two foundational beliefs that challenge conventional thinking about project management. First, it operates on the conviction that teams possess an innate ability to identify inefficiencies in their workflows and will naturally optimize given the opportunity. Second, it recognizes that since every project exists within its own unique context—different stakeholders, varying technical challenges, distinct team dynamics—the people closest to that work are best equipped to determine the most effective approach.

What makes this particularly compelling is how it reframes the role of methodology itself. Instead of providing a detailed playbook, Crystal offers principles and guidelines that teams can interpret and apply based on their specific circumstances. It’s less about following prescribed steps and more about creating conditions where effective collaboration can emerge organically.

What is the History of the Crystal Method?

The Crystal method emerged in 1991 when Alistair Cockburn, working with IBM, made an observation that would reshape how we think about software development frameworks. Rather than creating another rigid methodology with predetermined steps and checkboxes, Cockburn chose to study what actually made teams successful. His research revealed something counterintuitive: the most effective teams weren’t necessarily following the same processes, but they shared similar approaches to collaboration and communication.

This insight led Cockburn to develop what would become one of the original agile frameworks—though the term “agile” wouldn’t be coined for another decade. Instead of focusing on universal step-by-step development strategies, he concentrated on developing guidelines that would enhance team collaboration and communication, regardless of the specific technical approach.

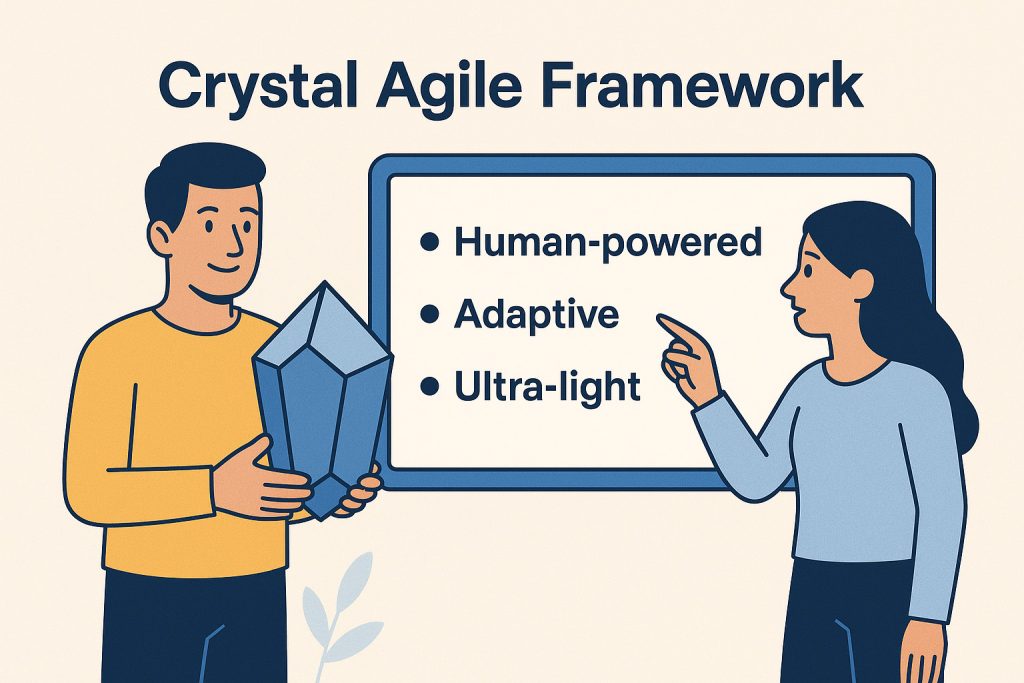

The characteristics that emerged from Cockburn’s work reflected this people-first philosophy:

- Human-powered: Projects should be flexible and tailored to accommodate the needs and preferred work modalities of the people involved

- Adaptive: The approach uses no fixed tools but can be altered to meet each team’s specific requirements and constraints

- Ultra-light: The methodology requires minimal documentation or reporting, maximizing time spent on actual development work

These principles represented a stark departure from the heavy, documentation-driven methodologies that dominated the early 1990s. Cockburn wasn’t just proposing a new framework; he was suggesting that maybe we’d been thinking about the whole problem backwards.

What are the Strengths and Weakness of Crystal?

The Crystal method’s people-first approach yields several distinct advantages that become apparent when teams are given the freedom to implement it authentically. The framework’s flexibility removes the friction that often exists between prescribed methodologies and actual work patterns, allowing teams to operate in ways that feel intuitive and effective rather than forcing natural collaboration styles into predetermined structures.

Crystal’s primary strengths include:

- Team autonomy: Allows teams to work in ways they determine to be most effective for their specific context

- Enhanced communication: Facilitates direct team communication, transparency, and accountability through organic rather than imposed structures

- Adaptive responsiveness: The flexible approach enables teams to respond swiftly to changing requirements without methodology constraints

This adaptability proves particularly valuable when dealing with evolving requirements, which is virtually guaranteed in any meaningful software project. Because Crystal teams aren’t locked into rigid processes, they can pivot naturally without having to first navigate through framework modifications.

However, Crystal’s greatest strength can also become its most significant limitation when not properly managed. The absence of predefined boundaries that other methodologies provide creates potential vulnerabilities that teams must actively address.

Crystal’s notable weaknesses include:

- Scope management challenges: The lack of pre-defined plans and boundaries can lead to scope creep if teams don’t establish their own controls

- Reduced organizational visibility: Minimal documentation requirements can create confusion and limit visibility for stakeholders outside the immediate team

Additionally, Crystal’s success depends heavily on team maturity and self-discipline. Not every team is ready for the level of autonomy and self-organization that the framework assumes, and some groups may benefit from more structure, at least initially.

Should You Use Crystal?

The decision to adopt Crystal requires careful consideration of both organizational culture and team readiness. This framework thrives in environments where there’s genuine trust in team capabilities and a willingness to accept that effective processes might look different from team to team.

Crystal works particularly well for organizations that have moved beyond the early stages of agile adoption and are seeking ways to reduce methodology overhead while maintaining collaborative benefits. It’s especially suitable for teams composed of experienced practitioners who communicate effectively and have developed strong technical disciplines. These teams can leverage Crystal’s flexibility to create working patterns that are genuinely optimized for their unique context and capabilities.

However, the framework is less appropriate for teams new to agile practices or organizations requiring detailed project visibility for compliance or stakeholder management purposes. The ultra-light documentation approach, while liberating for development teams, can create challenges for broader organizational needs, particularly when other departments require regular updates on project progress and decisions.

The framework’s emphasis on direct team collaboration around software development, combined with its de-emphasis on documentation and reporting, means that other teams across the organization may have limited visibility into progress and decision-making processes. Organizations considering Crystal must honestly assess whether they can accommodate this trade-off.

The Crystal method represents a mature perspective on agile development that recognizes the ultimate goal isn’t adherence to any particular framework, but rather creating environments where talented people can do their best work. It acknowledges that sustainable productivity emerges from optimized human interactions and the trust that develops when people are empowered to shape their own work environment. While this approach demands organizational sophistication and team maturity, it offers something that many heavily structured methodologies cannot: genuine space for teams to discover and evolve working patterns suited to their unique circumstances.

Conclusion

The Crystal method challenges us to reconsider what we really need from our development frameworks. In a world increasingly obsessed with process optimization and tool selection, Crystal suggests that our focus might be misplaced. Perhaps the most powerful framework is the one that gets out of the way, trusting in the collective intelligence of the team to find their own path forward. For organizations ready to embrace this level of trust and flexibility, Crystal offers not just a methodology, but a fundamentally different way of thinking about how great software gets built.