In the fast-paced world of software development, methodologies come and go like trends in fashion. Yet some approaches endure because they address fundamental challenges that persist across decades. Extreme Programming, or XP as it’s commonly known, represents one such enduring approach—a methodology that emerged from the recognition that traditional software development often failed both customers and developers in equal measure.

What sets XP apart isn’t just its emphasis on delivering quality software quickly, but its radical focus on making the development process itself more humane and sustainable. While many agile frameworks concentrate primarily on project outcomes, XP dares to ask a different question: what if we could build better software while simultaneously improving the lives of the people who create it?

What is eXtreme Programming?

eXtreme Programming stands as one of the most distinctive agile frameworks, distinguished by its dual commitment to customer satisfaction and developer well-being. Unlike methodologies that treat these as competing priorities, XP demonstrates that technical excellence and humane working conditions can reinforce each other in powerful ways.

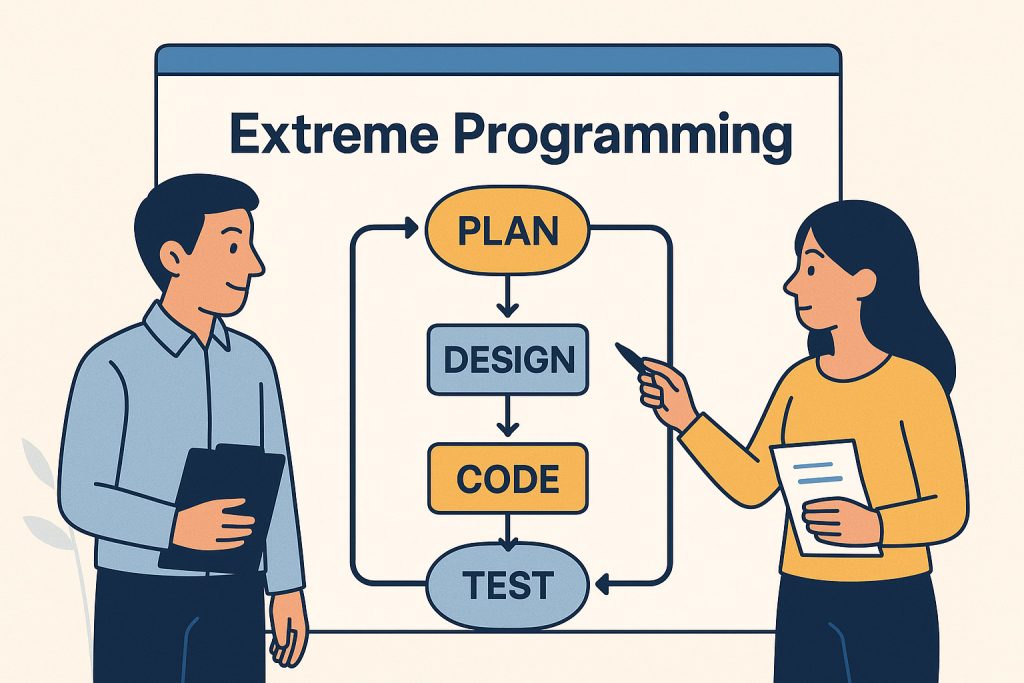

The framework operates on the premise that software requirements will change dynamically throughout a project’s lifecycle. Rather than viewing this as a problem to be solved, XP treats changing requirements as a natural characteristic of software development that should be embraced rather than resisted. This philosophical shift fundamentally alters how teams approach planning, design, and implementation.

XP thrives with small, collocated development teams that can communicate fluidly and make decisions quickly. The methodology assumes that face-to-face communication and spontaneous collaboration are essential ingredients for success, though modern practitioners have found creative ways to adapt these principles to distributed environments.

The framework’s emphasis on automated testing represents another core differentiator. XP teams don’t just write tests—they build comprehensive test suites that serve as both quality gates and living documentation. This investment in automated testing infrastructure enables the rapid iteration cycles that make XP’s dynamic approach to requirements feasible.

What’s the History of eXtreme Programming?

The story of Extreme Programming begins in 1996 with Kent Beck, a software engineer who had grown frustrated with the dysfunction plaguing many development projects. Beck observed teams struggling with unclear requirements, burnout from unsustainable work practices, and the persistent gap between what customers actually needed and what they received. His response was to create a lightweight agile framework that would address these systemic issues head-on.

Beck’s approach was methodical yet revolutionary. He identified twelve core practices that would form the backbone of XP, each designed to reinforce the others in a cohesive system. These practices emerged from Beck’s careful observation of what actually worked in successful software projects:

- The planning game – collaborative prioritization with customers

- Small releases – frequent delivery of working software

- Metaphor – shared understanding of system architecture

- Simple design – building only what’s needed now

- Testing – comprehensive automated test coverage

- Refactoring – continuous improvement of code structure

- Pair programming – two developers working together at one workstation

- Collective ownership – everyone can modify any part of the codebase

- Continuous integration – frequent integration and testing of changes

- 40-hour week – sustainable work pace

- Onsite customer – direct access to domain expertise

- Coding standard – consistent code formatting and conventions

Perhaps most importantly, Beck recognized that sustainable development required more than just technical practices. He articulated five fundamental values that would guide XP teams:

- Communication – keeping everyone informed and aligned

- Simplicity – doing the simplest thing that could possibly work

- Feedback – getting rapid input from code, customers, and team members

- Courage – making necessary changes and difficult decisions

- Respect – treating team members and customers with dignity

These values weren’t mere platitudes but practical guideposts that helped teams navigate the inevitable challenges of complex software projects. Since its introduction, XP has evolved and influenced countless other agile approaches, cementing its place as one of the foundational methodologies in modern software development.

Strengths and Weaknesses of eXtreme Programming

Understanding XP’s capabilities and limitations requires looking beyond surface-level benefits to examine how the methodology performs under different conditions and constraints.

XP’s strengths include:

The cost-cutting potential of XP emerges through multiple mechanisms that aren’t immediately obvious. While practices like pair programming might seem expensive because two developers work on the same code, teams consistently find that the reduced debugging time, improved code quality, and knowledge sharing more than compensate for the apparent inefficiency. The comprehensive test suites that XP teams build catch defects early when they’re cheap to fix, rather than allowing them to propagate to production where resolution becomes exponentially more expensive.

Team accountability in XP environments creates a positive peer pressure that motivates without requiring external oversight. When you’re pair programming, taking shortcuts becomes embarrassing. When the whole team owns the code, quality becomes everyone’s responsibility. This distributed accountability often leads to higher standards than any manager could impose from above, fostering a culture where excellence becomes self-reinforcing.

The methodology’s focus on sustainable practices and quality of life issues addresses one of the tech industry’s most persistent challenges: talent retention. Developers who work in XP environments often report higher job satisfaction, not because the work is easier, but because it feels more meaningful and manageable. The 40-hour work week isn’t just about being nice to developers—tired programmers make mistakes, and mistakes in software development are expensive.

XP’s weaknesses include:

The criticism that XP doesn’t sufficiently emphasize code quality might seem counterintuitive given its focus on testing and refactoring. However, this concern reflects a deeper issue: XP’s iterative approach means that early versions of features often prioritize functionality over elegance. While refactoring is supposed to address this technical debt, teams under pressure may defer these improvements indefinitely, leading to systems that work but are difficult to maintain.

XP’s emphasis on code over product design can create blind spots in the development process. While the methodology excels at building software efficiently, it provides less guidance on ensuring that the software being built is the right software to build. Teams can become so focused on technical execution that they lose sight of broader product strategy and user experience considerations.

The geographic distribution challenge poses significant obstacles for many modern development teams. XP’s most powerful practices—pair programming, osmotic communication, and the planning game—assume that team members can easily collaborate in person. While remote teams have developed workarounds, the energy and spontaneity of collocated XP teams remains difficult to replicate across time zones and video calls.

Should You Use eXtreme Programming?

The decision to adopt Extreme Programming isn’t simply a matter of comparing pros and cons—it’s about understanding whether your specific context aligns with XP’s assumptions and requirements. The methodology thrives in environments where requirements are genuinely uncertain and likely to change, making it particularly well-suited for innovative projects or rapidly evolving markets.

XP works best when you have access to customers or product owners who can provide ongoing feedback and make decisions quickly. The framework assumes that these stakeholders are available, knowledgeable, and decisive—assumptions that don’t hold true in many organizational contexts. When customer proxies or product managers fill this role imperfectly, the entire methodology can lose its effectiveness.

Technical infrastructure requirements for XP success include the ability to create comprehensive automated test suites and support continuous integration practices. If your project involves complex user interfaces, hardware integration, or systems where testing is difficult to automate, some of XP’s core practices may be less applicable.

Team composition matters enormously for XP adoption. The methodology requires developers who are comfortable with collaborative practices and willing to share knowledge freely. It also demands small team sizes—typically between two and twelve developers—where everyone can maintain awareness of the entire codebase.

The organizational commitment required for XP success extends beyond the development team. Leadership must be willing to protect the team from unsustainable demands and support the cultural changes that make XP practices effective. Half-hearted adoption often fails because the practices are designed to reinforce each other—implementing just a few XP techniques without the supporting values and environment typically yields disappointing results.

Consider XP when your project faces dynamic requirements, has access to engaged customers, can support comprehensive automated testing, and operates with a small collocated team willing to embrace collaborative practices. The methodology’s emphasis on sustainable pace and technical excellence makes it particularly valuable for long-term projects where team stability and code maintainability are crucial for success.

eXtreme Programming represents more than just another agile methodology—it embodies a philosophy that technical excellence and human well-being can and should reinforce each other. While the framework demands significant organizational commitment and works best under specific conditions, its core insights about sustainable development practices remain valuable regardless of the methodology you ultimately choose. The approach’s enduring popularity nearly three decades after its creation suggests that Beck and his collaborators identified something fundamental about what makes software development both effective and humane, demonstrating that we don’t have to choose between building great software and treating people well.