We live in an age of relentless demands. Your phone buzzes with notifications, your inbox swells with unread messages, and your mental to-do list grows faster than you can cross items off. It’s exhausting, and worse, it’s ineffective. You can spend entire days in constant motion and still feel like you’ve accomplished nothing meaningful. The problem isn’t that you’re lazy or disorganized—it’s that you’re drowning in choices about what deserves your attention.

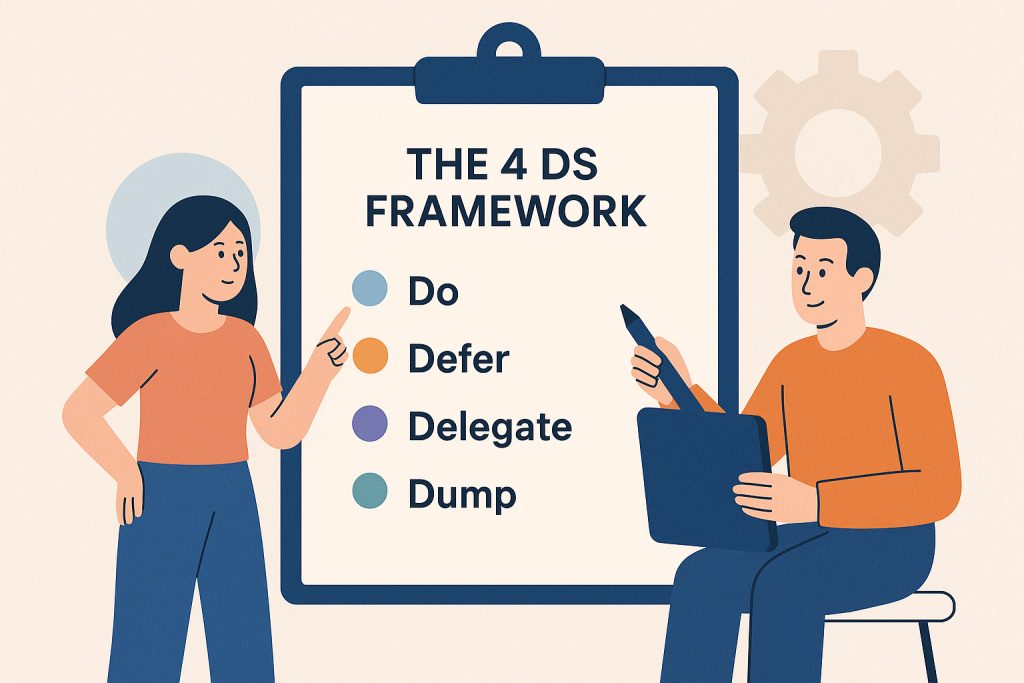

Enter the 4 Ds framework: Do, Defer, Delegate, Dump. Four simple categories that every single task can fall into. No elaborate systems, no complicated matrices, just four clear paths forward. The beauty lies in how this constraint forces clarity. Instead of endlessly shuffling priorities or letting anxiety decide what gets handled first, you make a concrete choice and move on.

Understanding the First D: Do It Now

Doing something immediately sounds like the default option, but it shouldn’t be. The whole point of this framework is recognizing that most things don’t require your instant attention, even when they feel urgent. So what belongs in the “Do” category? Tasks that genuinely need handling right now and won’t take long to complete.

There’s a useful rule here: if something takes two minutes or less, just do it. The mental energy required to organize, schedule, or hand off a tiny task actually exceeds the effort of simply getting it done. Reply to that quick email. File that document. Make that thirty-second phone call.

Beyond speed, immediate action makes sense for truly time-sensitive situations with real consequences. Your biggest client has an emergency. A system failure needs attention. A deadline looms in hours, not days. The key word is “genuine”—you need honest assessment of whether something really can’t wait or whether it’s just screaming loudly for attention.

The trap many people fall into is treating everything as a “Do” task. You become purely reactive, constantly firefighting, never getting to the work that actually moves your projects forward. The tasks you handle immediately should sit at the intersection of genuine urgency and actual importance.

The Second D: Defer for Strategic Timing

Deferring isn’t the same as procrastinating, though they can look similar from the outside. When you defer strategically, you’re acknowledging that a task matters but doesn’t need to happen right this moment. You’re making a conscious choice about timing rather than avoiding something uncomfortable.

This option shines for important work that isn’t urgent. Strategic planning, relationship building, skill development—these activities rarely scream for immediate attention but often determine long-term success. Sometimes you defer because you’re not in the right state to handle something well. Maybe you need more information before making a decision, or you’re too frustrated to respond diplomatically to a difficult message.

The Third D: Delegate to Multiply Your Impact

Delegation might be the most underused option in the entire framework, especially among capable people who pride themselves on reliability. There’s something satisfying about handling things yourself—you know they’ll get done properly, on time, exactly as you envision. But this mindset severely limits what you can accomplish.

The obvious delegation candidates are tasks someone else can do better than you. They have specialized skills you lack, or they’re closer to the relevant information. But there’s a more subtle category: tasks others could do adequately, even if not quite as brilliantly as you would. This is where perfectionism sabotages productivity.

Effective delegation requires more than just throwing work at someone. You need to provide context about why the task matters, clarity about what success looks like, and support in the form of resources or authority to complete it. Poor delegation—dumping something on someone’s plate without preparation—damages relationships and ensures future reluctance to accept delegated work.

The resistance to delegation often runs deeper than time constraints. When you hold onto tasks you could delegate, you might be protecting your sense of indispensability or your identity as someone who can handle everything. Recognizing these emotional dynamics is the first step toward moving past them.

The critical move when deferring is committing to specifics. “I’ll handle this later” is just procrastination wearing a professional mask. Instead, you need to block time on your calendar or add the task to a dated list that you actually review. Understanding your own energy patterns helps here—defer your most demanding cognitive work to whenever your mind operates best.

The Fourth D: Dump Without Guilt

This is the hardest option for most people, yet it’s often the right answer. Sometimes the best response to a task is simply not doing it at all. This requires acknowledging an uncomfortable truth: not everything that seems important actually is important, and not every request deserves your time.

Think about how many tasks accumulate through sheer momentum rather than necessity. That monthly report you’ve been generating for years might have been useful once, but perhaps nobody reads it anymore. The committee you joined when you were new might no longer align with your actual responsibilities. These things persist because stopping them requires a conscious decision.

Dumping also applies when someone else’s problem lands on your desk. When you’re competent, people naturally turn to you with their challenges. Learning to say “no” or “that’s outside my scope” isn’t selfishness—it’s boundary-setting that protects your ability to deliver on your real responsibilities.

Making Decisions: A Framework Within the Framework

Knowing the four categories is one thing. Knowing which category a given task belongs in requires judgment, and developing that judgment is where the real skill lies. Here are the key questions to ask yourself about each task:

- What happens if this doesn’t get done at all? If the honest answer is “nothing significant,” you’ve identified a strong candidate for dumping.

- Does this require my specific skills or authority? If someone else could handle it competently, it’s an opportunity for delegation.

- Is there a genuine deadline that demands immediate attention? This separates legitimate “Do” items from tasks you can defer without consequences.

Consider alignment with your larger goals and priorities. Just because something is urgent doesn’t make it important, and just because something matters to someone else doesn’t make it important to you. Every “yes” to something represents a “no” to something else, even if that something else is rest or creative space.

Another useful lens is return on investment. How much time, energy, or political capital will this task require, and what will you gain from completing it? Some tasks offer enormous value for minimal investment—clear “Do” candidates. Others demand substantial resources while delivering questionable benefits—prime candidates for the dump pile.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even people who understand the framework conceptually often stumble in practice. One frequent mistake is overusing the “Do” category, treating nearly everything as if it requires immediate attention. This creates the illusion of productivity—constant busyness—but often means neglecting important work that requires sustained focus in favor of urgent but less significant tasks.

Another trap is using “Defer” as a holding pen for things you feel guilty about dumping. Your deferred list becomes cluttered with items you’ll never actually do, creating persistent background anxiety as the list grows longer. An honest quarterly review of deferred items, ruthlessly dumping anything that’s sat there for months without action, helps prevent this accumulation.

The delegation pitfall takes two forms: either delegating poorly—dumping tasks on others without context or support—or failing to delegate at all because “it’s faster to do it myself.” That might be true for this single instance, but it’s rarely true over time.

People frequently struggle with the dump option because of sunk cost thinking. They’ve already invested time or energy into something, so abandoning it feels wasteful. But the sunk cost is gone regardless of what you do next. The only question that matters is whether continuing to invest in this task is the best use of your future time and energy.

When you consistently apply this framework over weeks and months, you begin to notice patterns in what kinds of tasks you’re drawn to doing immediately versus what you avoid, what you find easy to delegate versus what you cling to, and what you struggle to dump even when logic says you should. These patterns reveal your priorities, your insecurities, and your strengths in ways that can be genuinely illuminating. The framework becomes not just a productivity tool but a mirror that reflects how you spend your finite resources of time and energy, and whether those expenditures align with what you claim to value most.

Conclusion

The elegant simplicity of the 4 Ds offers a decision-making structure that cuts through the complexity of modern life. By reducing every task to one of four clear choices, the framework eliminates the paralysis that comes from unlimited options while building the decisiveness that separates effectiveness from mere busyness. Yet the real transformation happens not in learning the categories but in developing the judgment to apply them wisely and the courage to make unpopular choices when necessary. What you choose to do immediately, postpone strategically, entrust to others, or simply let go reveals not just how you work, but what you genuinely value in a world that will always demand more than you can possibly give.